Conversation / Jonathan Cleaver

Textile researcher Jonathan Cleaver talks about Carpets of Distinction, Stoddard-Templeton archive and the threads of his current research into carpet weaving

February 2021

2012 marked the centenary year of Dovecot Studios and to celebrate one hundred years of production, Panel worked with Dovecot to curate the exhibition Carpets of Distinction. Together we commissioned six new limited-edition works, inspired by the archive collection – housed at the University of Glasgow and the Glasgow School of Art – of two of the most significant Scottish textile companies of the twentieth century: Stoddard International Plc and James Templeton & Co Ltd. Within a specially constructed showroom, designed by Steff Norwood and HIT (Lina Grumm & Annette Lux), the commissioned rugs offered new perspectives and connections to the Stoddard-Templeton Archive, making explicit an interwoven chronology between the factories, the artists and Dovecot.

Representing a broad range of concerns and distinct in their design, the hand-tufted rugs took inspiration from the history of carpet design through reference to traditional motif and pattern as well as practical and aesthetic function. Jonathan Cleaver was the weaver at Dovecot who worked closely with the artists – John Byrne, Nick Evans, Ruth Ewan, Alasdair Gray, Nicolas Party, Joanne Tatham and Tom O’Sullivan – to produce each of the woven rugs. Since leaving Dovecot in 2017, Cleaver has maintained focus on the Stoddard-Templeton Archive through his ongoing PhD research in technical innovation and the development of carpet design in the companies’ design histories.

We worked together when you were a weaver at Dovecot. How did this commissioning project with Panel differ from other Dovecot projects?

Dovecot’s weavers are well practiced at working closely with artists and designers to translate their ideas into textile artworks. The unique part of this commission was Panel’s work to gather everyone around the extraordinary archives of the Stoddard-Templeton group of carpet manufacturers. I remember the real sense that the curators, archivists, artists, and designers all had valid perspectives on this resource. I was actually quite surprised that all the participants wanted to keep the objects recognisably as rugs rather than making more drastic interventions or deconstructions. Possibly, that was influenced by the presence of the archives as a massive store of prior commercial work.

Whilst working with the commissioned artists on each individual rug, did you observe any interesting crossovers or differences in the way they approached the brief, or the Stoddard-Templeton Collection?

Each of the commissioned artists had a unique working practice so I needed to respond to their thoughts about their work, and about working in a medium that was new to them. I was glad that we were making work that was distinctively theirs, rather than the artists being overwhelmed by the archive. Ruth Ewan keyed into labour organisation; Nick Evans was struck by the pervasiveness of pattern making. I also tried to make sure that textures, materials and gestures were relevant to each piece individually, rather than just applying the artists’ imagery to a standard product. For Nicolas Party’s bodycolour sketch we sat down together to make a hundred, or more, blends of coloured yarns to create painterly effects. In Tatham & O’Sullivan’s rug, there is a sort of pun in the way that I hand-crafted the inset footprints from industrially produced carpeting. Some of this meant experimenting with techniques. To preserve the flow of Alasdair Gray’s calligraphic script, for instance, I inlaid a particularly soft cotton cord, which is sold as “magicians’ rope” for sleight of hand tricks. It felt appropriate in relation to the transformations in his wider work.

We love the text you wrote to introduce Carpets of Distinction and the idea of rugs and carpets having split identities. What do you think it is about the nature of rug and carpet design and production that makes this so?

The main point of tension in the carpets is whether their function is as a furnishing or an aesthetic object; are they on the floor or the wall? How much should we elevate them? There is something stubbornly everyday and underfoot about carpets in British culture that makes them disarming, even though they can be glorious, sensual, uncanny objects.

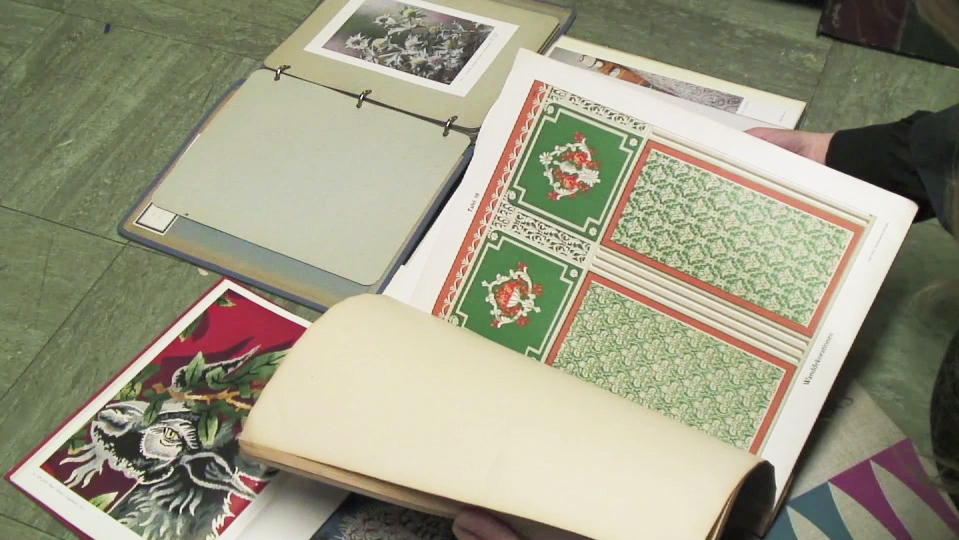

Several of the Carpets of Distinction rugs have a humorous element, and maybe there’s a touch of absurdity in the brief for artist-designed rugs. Since I have got to know the Stoddard-Templeton archive, I wonder if surrealist humour seeps in from there too. It is so vast and heterogenous in its content and imagery. Non-sequiturs are the norm, time periods are mixed up, and images are divorced from their cultural origins: ultra-modern and historicist, Persian and French, 1890s and 1980s. The archives were accumulated as a working resource by designers with a deep knowledge of patten and of their company’s heritage. That arrangement has been preserved with great care, but an understanding of it is harder to recapture. The archivists at the University of Glasgow and Glasgow School of Art have done astonishing work cataloguing the collections, making them findable, and conserving them for the future. But as a former working collection, the records don’t necessarily respond readily to the questions you want to ask them. It has taken me a lot of effort to make connections between records in the archive and to build them into meaningful arrangements. I wonder if the artists in Carpets of Distinction sensed that too, and the touches of absurdity are prompted by the experience of encountering the archives.

You used the gun-tufting method to realise the artists’ designs as tufted rugs. What does this method offer, in terms of malleability, to an individual’s creative concept, as opposed to hand-knotting or more industrial forms of weaving?

The industrial carpet-weaving techniques used by the firms in the Stoddard-Templeton group were ingeniously designed to balance flexibility of pattern design with efficient production. Crucially, they worked best for making large batches of a design, which would be difficult to match with artists’ exploratory methods of working. The gun-tufting method works on a much more intimate scale and is great for unique or small edition pieces. It is a tool that makes the pile of the carpet by shooting strands of yarn through a backing textile, leaving plenty of opportunity for the tufter to work intuitively. In that sense the tufting gun is a drawing tool, and the potential to make really gestural marks was essential in the way that I used it for John Byrne’s rug. The design is a characterful double self-portrait of an older Byrne confronting himself at the age when he briefly worked for the carpet firm, A. F. Stoddard and Co. Using the tufting gun, I could make improvised marks, moving with my whole body, and looking directly at Byrne’s scraperboard drawing. The same design would take months to plan and make using traditional hand-knotting. Gun-tufting can also be manipulated to give different effects: for example, the painterly colour blending in Nicolas Party’s landscape design, or the deep, chunky pile that gives Tatham & O’Sullivan’s rug a more sculptural presence.

Former Stoddard and Templeton showrooms were referenced by Panel in the exhibition scheme, foregrounding a once-booming industry whilst also highlighting the commerciality of the contemporary commissions. Can you say a little about the artistic direction that was employed within the original showrooms and sales catalogues, to encourage potential buyers?

In Carpets of Distinction, I really appreciated the way that Panel carried their observations of the archive through to the graphic design and staging of the exhibition. Their method of investigating Stoddard and Templeton’s work was to make a space that exhibited the archive and was also a commercial display of the new rug products. It didn’t hide the commercial impetus that produced the records that are now preserved in the archives. Carpets can be awkward objects to display because of their size and orientation, so both Stoddard and Templeton and Panel found novel ways of making them engaging to look at, whilst keeping them more or less flat to the floor. Templeton’s own exhibition displays were on a grand scale and often reflected the mood of the times. Their orientalist pavilion in the 1901 Glasgow International Exhibition, for example, rather crassly used the styles of Islamic architecture for exotic effect. Whereas their modernist structures at the Scottish Industries Exhibitions in the 1950s give us a more comfortable impression of post-war optimism in design. Templeton also tried eye-catching ways of conveying carpets in print, like flocked lithographs in the 1910s, and transparent overlays of room-sets and carpets in the 1970s.

Your current PhD research is focused specifically on the Stoddard-Templeton Collection held jointly by the University of Glasgow Archives and The Glasgow School of Art Archives and Collections. What in particular have you been exploring within this vast collection?

It really is a vast collection. I have been researching the overlap between design practice and the weave-construction of carpets in Templeton’s work before World War II. The design drawings are so visually rich that it is tempting to think of them as artworks, but they are technical drawings first of all, related to schematics or blueprints. Part of my task has been learning to ‘read’ pattern drawings using the same early 1900s training texts that trainee designers would have used. There has been an understandable bias in the past to focus on extraordinary carpets, particularly those designed in progressive styles by well-known names. That has misrepresented the very skilled work of the company’s designers, who are less well documented. It has underplayed the cultural impact of less prestigious styles such as ‘reproduction oriental’ rugs and plain-coloured carpets, both of which Templeton made in extraordinary quantities. I have levelled out some of those qualitative judgements by thinking about the carpets from the point of view of weave-construction – no matter what the imagery, everything had to work on the loom. Carpets of Distinction first opened the archive to me, and my research has made me realise that there are hundreds more stories hidden in the pile of carpet weaving.

Jonathan Cleaver makes and researches textiles. Formerly a Master Weaver with Dovecot, Edinburgh, his PhD research on the carpet manufacturer James Templeton and Company is funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council with the Scottish Graduate School for Arts and Humanities.

Interview by Laura Richmond